Exploring Adin Steinsaltz, Renate and Geoffrey Caine, and the Amphibious Jew

In this article I will be linking the understanding of the implications of the research in neuroscience for education explored by Caine and Caine with an insight I have amplified from Adin Steinsaltz, noted Jewish scholar of Talmud and Jewish mysticism (this insight was passed on to me by Rabbi Barbara Penzer). I call this concept the amphibious Jew. Underlying the confluence of both these texts is a deep appreciation for the value of the immersive, water-like quality of the initial stages of curious and engaged learning. In an article by Velvet Green, “Curiosity and the Desire for Truth”, she links this “curiosity” to the primal experience of birth:

I’ve often marveled at the basic miracle of birth. Every one of us, in our mother’s womb, was a real aquatic creature before we were born. We were surrounded by water . . . our lungs were folded up like a fan, not in use but getting ready. . . . When the child is born, no matter how long the mother labors, “birth” is practically instantaneous. Once the child’s head emerges, it must take its first breath; it’s now a land creature, not an aquatic one. . . . How does it happen? A most amazing chemical miracle takes place, starting during the labor of the mother.

Caine and Caine and the Brain

In Natural Learning in a Connected World (2011) the authors introduce us to the notion to their own understanding of the relationship between learning and doing. We know the brain moves along a perception-action continuum, always looking for information and connections to process, always threatened by the demon of abstraction stripped of sensory experience. The three stages of the unfolding model are:

- Relaxed Alertness

- Orchestrated Immersion in Complex Experience

- Active Processing and Reflection

Before examining each of the three steps, we take a look at the gestalt of the teaching. Perhaps the parade example of utilizing this approach is the contrast Caine and Caine offer between traditional ways of teaching nutrition (learning a pre-established vocabulary and set of concepts) and the launch of their unit on nutrition. Caine and Caine begin by having their students experience new foods and record the tastes and smells of the food. Eventually curiosity leads them down the esophageal passageway into their stomachs, where their learning is then scaffolded by an exploration of various digital spaces and a set of guiding questions generated by the students.

Each of the three phrases also helps provide elegant midrash on the current emphasis on Jewish experiential learning. Relaxed alertness reminds us that educational experience cannot effectively occur in a neurological vacuum. Students can’t or shouldn’t be simply thrown into new experiences. A culture and atmosphere of trust and engaged exploration needs to be created in the classroom. Any hint of “fight or flight” will undermine the process.

The next phase – orchestrated immersion in complex experience – is demanding as well. Orchestration already hints that the role of the teacher has been shifted from pedagogue to the orchestrator of educational experience, the guide on the side as it were. Immersion is also critical. There is no direct transfer of knowledge along a corridor of teaching. The content always needs to be richer and deeper than the product the learner will ultimately develop. Access to digital resources and new educational technologies of the kind described by Kolb (Learning First, Technology Second) is one of the best ways to initiate such orchestrated immersion.

Further, the experience needs to be richly complex. Here is where ideas and concepts drawn from disciplined knowledge is critical. Once immersed and engaged, the mind of the learner will beg to be stretched by new ideas and values. No single experience will do. Even the proverbial experience of being slaves in Egypt will need to have dimensions of nuance and challenge included in the learning challenge. The brains attraction to paradox, challenge, and complexity needs to be honored.

Adin Steinsaltz and the Amphibious Jew

Adin Steinsaltz is a revered scholar of Talmud and Jewish mysticism, but also, importantly, a person with some background in biology. Steinsaltz once observed in a lecture given in Jerusalem in 1993:

All creatures live in water. The difference between sea creatures and land creatures is that land animals draw the water into themselves.

Undoubtedly, Rabbi Steinsaltz is aware as he writes this of a classical Jewish midrash told by Rabbi Akiva. The story begins with a conversation between a fish and a fox. The plot is clear. The fox would love for the fish to jump out of the pond becomes the fox’s supper. Why does the fish refuse? Like the Jew in relationship to the living waters of Torah, the fish cannot exist outside of the water.

Returning to Steinsaltz’s epigram, there are two vital dimensions to all educational experience. One is marine. Engagement is the major trope of this work. It points to the importance of immersive venues where one can experience Judaism naturally and organically. It is aligned with much of what we have learned works in Jewish education in venues such as camp, Israel trips, retreats and some forms of early childhood education. Perhaps preeminently it is present in homes where Judaism is practiced from birth.

The other mode is mammalian, where Jews consciously journey to the house of their friends, their synagogues and communities to experience a very mindful Judaism that can guide them in creating spiritual connections as well as applying Jewish values to contemporary ethical dilemmas. Meaning-making is its major trope.

These two modes will remind many readers of two important voices in contemporary dialogues about experiential learning. The first is Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s notion of “flow”. Initially, our richest educational experience has a marine-like quality of moving naturally through the medium that educates. When “rich complexity” is available and “well-orchestrated”, the learner is so engaged with the learning that it is entirely focused and gripping. It feels a little like the chorus of the Broadway song from Annie Get Your Gun – “doin what comes naturally.”

Eventually the orchestration of these experiences will begin to borrow more from the work of Lev Vygotsky. As Kolb reminds us, it is the richer and more complex understanding of subject matter that matter most. The notions of scaffolds is the tool of choice for projects as we move from spontaneous to scientific concepts and create the cognitive and valuational structures that give substance and form to the educational flow initiated in a marine fashion. Wisely used, technology provides extraordinary tools for such extension and deepening of the learning. In a way this mirrors Vygotsky’s insights about the relationship between spontaneous and scientific concepts. While in theory it is possible to precede top-down from the scientific to the spontaneous use of concepts, the process works best in the other direction, from bottom up.

In working its slow way upward, an everyday concept clears a path for the scientific concept and its downward development. It creates a series of structures necessary for the evolution of a concept’s more primitive, elementary aspects, which give it body and vitality. Scientific concepts, in turn, supply structures for the upward development of the child’s spontaneous concepts toward consciousness and deliberate use. (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 194)

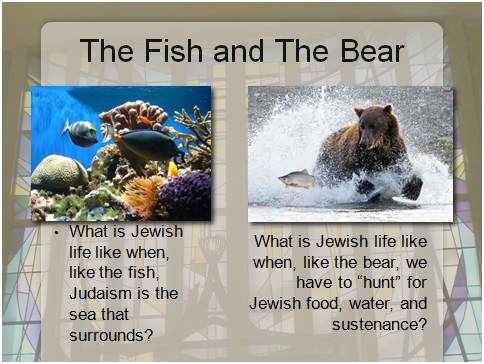

Here is a picture that is linked to a question Jewish educators might ask as we create Jewish experiences for children:

Because each of these modes of Jewish existence has deep value and importance, it is critical that Jews have access to each. Neither the mammalian, self-guiding Jew, nor the marine Jew for whom Judaism is as natural as a fish swimming in water, can stand alone. We need to guide the next generation in becoming amphibious creatures who can alternately live in both land and water Jewish environments. Just like Froggy:

I believe Caine and Caine suggest the kind of conditions that must be created for students as they move back and forth between marine and mammalian life, and become both marine Jews who move naturally through Jewish environments, and mammals who use their analytic powers to process complex Jewish experience.

I believe Caine and Caine suggest the kind of conditions that must be created for students as they move back and forth between marine and mammalian life, and become both marine Jews who move naturally through Jewish environments, and mammals who use their analytic powers to process complex Jewish experience.

Further, there are implications for curriculum designers, funders, and educational entrepreneurs who want to create the conditions for effective Jewish learning and experience.

To further that exploration, I formulate the following existence proofs of what it means to take Froggy seriously;

You know you are an educator embracing the concept of the amphibious Jew when_________:

–– as a Jewish educator, you quite naturally think about the opportunities in your school year to offer immersive Jewish experiences (summer ulpanim, retreats, etc).;

–– you appreciate both the experience of Jewish naturalness and normality in Israel and the kavana/intentionality required to make Jewish time and space in your North American Jewish life;

–– you make sure that each learning experiences you are creating of some element of marine and mammalian Jewish life in them;

–– you have examined the Jewish life-cycle for its natural rhythms of marine and mammalian possibilities (e.g., when do learners move into stages where the amphibious or mammalian mode is the best pathway to rich learning for this age /stage learner?);

–– you can reflect on your own biography as a Jewish learner and see both the marine and mammalian influences

–– you appreciate the learning of Hebrew as itself an example of the amphibious cycles (first being surrounded by the language, then learning its structures and tools, hearing, speaking, reading, and writing;

–– upon rereading the important chapter on Jewish education in Mordecai Kaplan’s Judaism as a Civilization, you can understand why it might be retitled “Mordecai Kaplan’s Aquarium”

Lastly, the final exam for blossoming amphibious Jewish educator looks like this: They read the famous Talmudic story contrasting the learning styles of Rabbi Hiya and Rabbi Hanina with creative indifference rather than sharp advocacy. In the tale, Hanina is said to have restored the whole Torah through the power of his analytic and dialectic powers. Hiya’s claim is that he would make sure the Torah is not forgotten in the first place by making his learning hands-on and empowering and linked to the rhythms of Jewish living. Resisting our impulse to lionize Hiya because Jewish education seems so impossibly dry and analytic, we would insist in the name of Froggy that both modes are critical –– and our job is to create creative synergy between them.